Background

About half a year ago, I wanted to create a simple, tag-based blog. A space where I can talk about any topic. and let readers filter by their interests. but i quickly benched that idea because maintaining an active blog sounded like a manual hassle at the time.

That changed months later. When I started my note taking journey in Obsidian. I enjoyed the writing process, I loved actively looking for more information to learn. Each note that I wrote left a taste of more. To understand what I mean, I have a post that explains Why I have a second brain in Obsidian.

I realized the best way to blog wasn’t to use a separate platform, but to turn Obsidian, the tool I am already familiar with into my publishing engine.

The end result is a pipeline that made it possible for me to write this blog post inside Obsidian and with one button run a script that publishes the post into my website.

The pipeline was heavily inspired by NetworkChuck and 4rkal.

What We Will Make

The end goal is a high-performance static website. a professional blog that lives on the web but is managed entirely from your Obsidian.

We will go into how can have it look exactly like my blog or have your own design. The best part is, You don’t need any prior programming knowledge as I’ve already done the heavy lifting with the scripts, so you can focus on the writing.

For those with basic web development skills, the system is fully customizable (For example, I created my own theme for this blog). But don’t worry if you are not a coder. there are hundreds of beautiful templates ready for you to use (we’ll dive into those shortly).

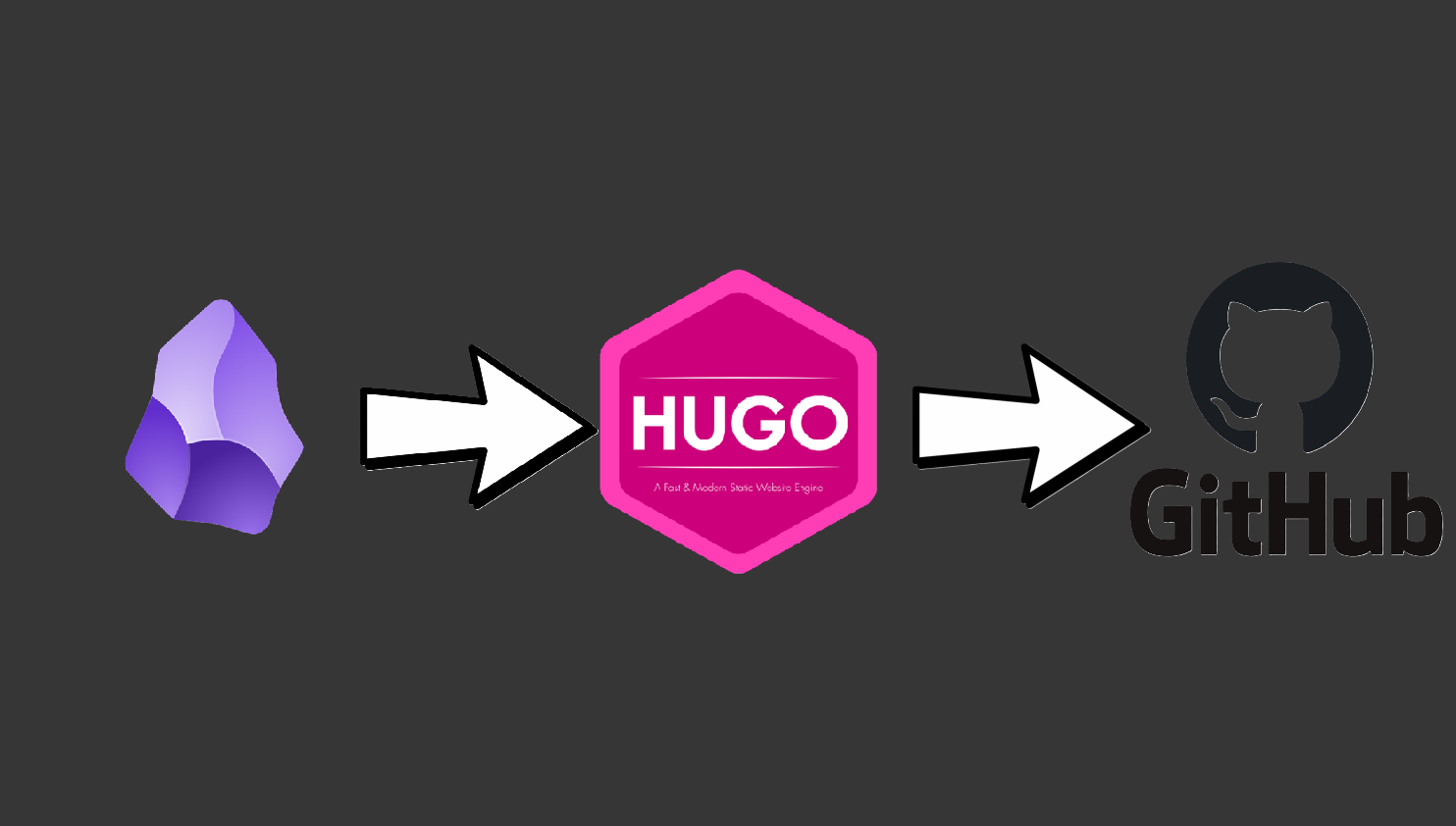

Meet the Players

Obsidian (The Editor): This is where the magic happens. It’s our primary writing environment where we create and manage our

.md(Markdown) notes.Hugo (The Engine): Hugo is a powerful static site generator. It takes your raw Obsidian notes and transforms them into clean HTML that web browsers can understand. It also handles the “logic” of your site. meaning it automatically organizing your tags, posts, and page routing based on your settings.

GitHub (The Vault): We use GitHub to store your website’s code and configuration and versioning in the cloud.

A note for non-programmers: While using GitHub might feel like a “developer thing,” it is essentially a high-powered version control system. Think of it as a secure backup that allows you to see every change you’ve ever made. I highly recommend setting up an account. It’s the industry standard for a reason.

The Pipeline

Here is exactly what happens when you finish writing and want to hit “Publish.”

We use the an Obsidian plugin such as Shell command or Script Launcher to execute our custom script.

That’s all. With one click, that script executes the following “Automated Routine”:

- Sync your Obsidian

postsfolder with your blog’s (Hugo’s)contentfolder. - Sync any images used in your Obsidian to your blog’s

static/imagesfolder. - Build the site (Transform all md files into HTML and make the website).

- Uploads the finished compiled site to your GitHub repository into a dedicated branch called

deploy. This ensures your Obsidian vault stays private and organized, while your website stays updated and professional.

Pro Tip: While you can technically install Hugo directly inside your Obsidian vault, I highly recommend keeping them separate as I do. It keeps your personal notes clean and prevents your blog’s technical files from cluttering your writing space.

Obsidian formatting

Your posts in obsidian need to use a frontmatter. Hugo will use that frontmatter to know more metadata about your post.

For this very reason I have a Base Post template in Obsidian that I will share here:

---

title: Untitled

date: 2025-12-17

tags:

- mytag

draft: true

description: "A brief summary of the post"

---

If you haven’t used this before, don’t worry. once you paste it in Obsidian, it recognizes the text as a “Properties” view, making it very easy to fill out.

Important Note on Thumbnails: You’ll notice my template doesn’t have a

thumbnail:field. That’s because the script I’ve built will automatically look into your Obsidian attachments directory for an image with the exact same name as your post and sets it as the thumbnail for you.

Downloading and configuring Hugo

To get the core engine up and running, I followed NetworkChuck’s excellent guide. He breaks down the installation of the necessary prerequisites (Git, Go, and Python). And he shows you how to initialize your very first Hugo project.

Since his explanation is so clear and visual, I recommend watching the setup portion of his video here: I started a blog… in 2024

Follow his steps until you have a basic site generated. However, before you move on to his deployment steps, let’s talk about the specific improvements I’ve made in my pipeline. While Chuck’s method is amazing, I’ve tweaked the logic to handle my needs.

The images script

Here is the “heavy lifting” I promised. While the script in the original NetworkChuck tutorial is a great start, it has a few limitations that I wanted to solve:

- Image Bloat: Chuck’s script copies images over, but if you delete an image from your post later, the file stays in your blog folder forever. My version includes a cleanup routine that removes any image from your website that isn’t actively referenced in a post.

- Automatic Thumbnails: This script looks at your post title, and checks your attachments folder for a matching image. If it finds one, it automatically sets it as your thumbnail.

Please note that this script is designed to work on windows. I haven’t tested it on Mac or Linux.

import os

import re

import shutil

from urllib.parse import unquote

# Paths (using raw strings to handle Windows backslashes correctly)

posts_dir = r"C:\Users\livou\Documents\Programming\Personal\manablog\content\posts"

attachments_dir = r"G:\My Drive\Obsidian\Rioru\attachments"

static_images_dir = r"C:\Users\livou\Documents\Programming\Personal\manablog\static\images"

# Ensure static/images directory exists

os.makedirs(static_images_dir, exist_ok=True)

# Track all referenced images across all posts

referenced_images = set()

def slugify(text):

"""Convert text to URL-friendly slug (similar to Hugo's urlize)"""

# Convert to lowercase

text = text.lower()

# Replace spaces and special chars with hyphens

text = re.sub(r'[^\w\s-]', '', text)

text = re.sub(r'[-\s]+', '-', text)

# Remove leading/trailing hyphens

text = text.strip('-')

return text

def extract_title_from_frontmatter(content):

"""Extract title from YAML frontmatter"""

# Try YAML frontmatter (--- or +++ delimiters)

frontmatter_pattern = r'^(?:---|\+\+\+)\s*\n(.*?)\n(?:---|\+\+\+)\s*\n'

match = re.match(frontmatter_pattern, content, re.DOTALL)

if match:

frontmatter = match.group(1)

# Look for title field

title_match = re.search(r'^title:\s*["\']?(.+?)["\']?\s*$', frontmatter, re.MULTILINE)

if title_match:

return title_match.group(1).strip()

return None

def find_title_based_image(title_slug, attachments_dir):

"""Find image in attachments folder that matches the title slug"""

if not os.path.exists(attachments_dir):

return None

image_extensions = ['.png', '.jpg', '.jpeg', '.webp']

# Check for exact match with slug

for ext in image_extensions:

potential_image = f"{title_slug}{ext}"

image_path = os.path.join(attachments_dir, potential_image)

if os.path.exists(image_path):

return potential_image

# Check for case-insensitive match

for filename in os.listdir(attachments_dir):

if not any(filename.lower().endswith(ext) for ext in image_extensions):

continue

# Get filename without extension

name_without_ext = os.path.splitext(filename)[0]

name_slug = slugify(name_without_ext)

if name_slug == title_slug:

return filename

return None

# Step 1: Process each markdown file in the posts directory

for filename in os.listdir(posts_dir):

if filename.endswith(".md"):

filepath = os.path.join(posts_dir, filename)

with open(filepath, "r", encoding="utf-8") as file:

content = file.read()

# Extract title and find title-based image

post_title = extract_title_from_frontmatter(content)

title_image_dest = None

if post_title:

title_slug = slugify(post_title)

title_image = find_title_based_image(title_slug, attachments_dir)

if title_image:

# Copy title-based image to static/images with slugged name

source_path = os.path.join(attachments_dir, title_image)

# Use the extension from the found image

_, ext = os.path.splitext(title_image)

dest_filename = f"{title_slug}{ext}"

dest_path = os.path.join(static_images_dir, dest_filename)

if os.path.exists(source_path):

shutil.copy(source_path, dest_path)

title_image_dest = dest_filename

referenced_images.add(dest_filename)

print(f"Copied title-based image: {title_image} -> {dest_filename}")

# Step 2: Find all image links in Obsidian format:  or

# Match the entire pattern including optional ! prefix

# Support multiple image formats

image_pattern = r'!?\[\[([^]]*\.(?:png|jpg|jpeg|webp))\]\]'

images = re.findall(image_pattern, content)

# Also check for already-processed images in Hugo format:

processed_image_pattern = r'!\[[^\]]*\]\(/images/([^)]+)\)'

processed_images = re.findall(processed_image_pattern, content)

# Add all referenced images to the set

for image in images:

referenced_images.add(image)

for processed_image in processed_images:

# Decode URL-encoded image names (e.g., %20 -> space)

decoded_image = unquote(processed_image)

referenced_images.add(decoded_image)

# Step 3: Replace image links and ensure URLs are correctly formatted

for image in images:

# Prepare the Markdown-compatible link with %20 replacing spaces

markdown_image = f"})"

# Replace both ![[image]] and [[image]] formats

content = re.sub(rf'!?\[\[{re.escape(image)}\]\]', markdown_image, content)

# Step 4: Copy the image to the Hugo static/images directory if it exists

image_source = os.path.join(attachments_dir, image)

if os.path.exists(image_source):

shutil.copy(image_source, static_images_dir)

# Step 5: Write the updated content back to the markdown file

with open(filepath, "w", encoding="utf-8") as file:

file.write(content)

# Step 6: Remove images from static/images that are no longer referenced

if os.path.exists(static_images_dir):

static_images = set(os.listdir(static_images_dir))

images_to_remove = static_images - referenced_images

for image_to_remove in images_to_remove:

image_path = os.path.join(static_images_dir, image_to_remove)

try:

if os.path.isfile(image_path):

os.remove(image_path)

print(f"Removed unused image: {image_to_remove}")

except Exception as e:

print(f"Error removing {image_to_remove}: {e}")

print("Markdown files processed and images synced successfully.")

How to configure it:

Before running the script, make sure you update these three paths at the top of the file to match your computer’s setup:

posts_dir: Where your Hugo content lives.attachments_dir: Your main Obsidian attachments folder.static_images_dir: Thestatic/imagesfolder inside your Hugo project.

The big script

In NetworkChuck’s video, he provides a great foundational script. I’ve rewritten Step 8 to use a Git and push the end result into a deploy branch without cluttering it with your configuration files or Python scripts.

Note, This script also only works on Windows.

# Step 8: Push the public folder to the hostinger branch using subtree split and force push

$TargetRemoteBranch = "deploy"

$TempSplitBranch = "temp-split-branch"

Write-Host "Deploying to GitHub Deploy..."

# Check if the temporary branch exists and delete it

$branchExists = git branch --list "$TempSplitBranch"

if ($branchExists) {

git branch -D $TempSplitBranch

}

# Perform subtree split

try {

git subtree split --prefix public -b $TempSplitBranch

}

catch {

Write-Error "Subtree split failed."

exit 1

}

# Push to hostinger branch with force

try {

git push origin "$($TempSplitBranch):$($TargetRemoteBranch)" --force

}

catch {

Write-Error "Failed to push to hostinger branch."

git branch -D $TempSplitBranch

exit 1

}

# Delete the temporary branch

git branch -D $TempSplitBranch

Write-Host "All done! Site synced, processed, committed, built, and deployed."

Final Steps & Launch

Once you have this script saved, simply point your Obsidian Shell Launcher or Script Launcher plugin to this .ps1 file.

Now, whenever you finish a post in Obsidian, you just hit one button. The script will sync your text, and media, build the site, and push it to your GitHub repository.

Theming

In his original video, NetworkChuck used a terminal-style theme. While it has a certain “hacker” charm, it’s not exactly the best for readability or a modern professional look.

One of the best things about Hugo is how easy it is to swap your site’s entire appearance. You can browse thousands of options at the Hugo Themes Gallery, but if you want a head start, I recommend these three:

- Mana Theme: This is the theme I personally designed and the one you are looking at right now. It’s built to be clean, fast, and specifically optimized for this Obsidian pipeline.

- PaperModX: Very minimalistic theme

- Blowfish: Clean look, customizable.

Your theme choice won’t change how your pipeline works, so feel free to experiment until you find the look that fits your brand. You can also have multiple themes saved and change them in hugo.toml whenever you want.

Deployment

If you followed the original tutorial, you saw NetworkChuck using Hostinger. While they are a solid choice, keep in mind he was sponsored by them, you are by no means locked into their ecosystem.

Because our script pushes production-ready version of your site to the deploy branch on GitHub, you can host your blog almost anywhere.

Here are a few popular alternatives:

- GitHub Pages: Since your code is already on GitHub, this is the most seamless option. It’s free and very reliable.

- Netlify: Extremely beginner-friendly. You just point it to your

deploybranch, and it handles the rest. - Vercel: Similar to Netlify, offering incredible speed and a great global CDN.

The beauty of this pipeline is that your “source of truth” stays in Obsidian. If you ever decide to switch hosting providers, you just point the new service to your GitHub repo, and your site is back.